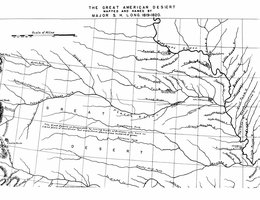

Major Stephen Long coined the phrase during his expedition to the Great Plains in 1819-20. His journey was only the third major exploration of the Louisiana Purchase since the U.S. bought it from France in 1803. Long’s findings were followed avidly by the public.

Who was right? Maj. Stephen H. Long called the plains "The Great American Desert". Fifty years later, Prof. Samuel Aughey of the University of Nebraska boasted that the state was a veritable garden by declaring: "Rainfall follows the plow."

Long thought the plains region was a desert because it didn’t support the kind of trees and plants that were familiar to him. So, he concluded that the region was "almost totally unfit for cultivation." Long was both wrong and right. Over the next 150 years, farmers in some locations would prove him dead wrong by producing abundant crops. But, in other parts of the Plains and in other years, people would find Long’s assessment deadly accurate.

Major Stephen Long wrote:

" . . . [The Great Plains region] is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. Although tracts of fertile land considerably extensive are occasionally met with, yet the scarcity of wood and water, almost uniformly prevalent, will prove an insuperable obstacle in the way of settling the country. . . . This region, however, . . . may prove of infinite importance to the United States, inasmuch as it is calculated to serve as a barrier to prevent too great an extension of our population westward, and secure us against the machinations or incursions of an enemy."

Long’s editor, Edwin James, expanded on Long’s observations:

"We have little apprehension of giving too unfavorable an account of this portion of the country. Though the soil is in some places fertile, the want of timber, of navigable streams, and of water for the necessities of life, render it an unfit residence for any but a nomad population. The traveler who shall at any time have traversed its desolate sands, will, we think, join us in the wish that this region may forever remain the unmolested haunt of the native hunter, the bison, and the jackal."

From Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains Performed in the Years 1819, 1820, published in Philadelphia in 1823, compiled by Edwin James from notes by Long, zoologist Thomas Say & others. Reprinted in Reuben G. Thwaites ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1846, 32 vols. (Cleveland, 1904-1907).

The Plains were hard to live on. Many of the newcomers were used to living in villages and then walking or riding out to their fields to farm. But the Homestead Act required those claiming the land to live on it, and the act forced settlers to farm the land in 160-acre plots. So, each settler was at least 1/4-mile away from his or her nearest neighbor. In some parts of the West, you might find yourself tens of miles away. A horse, if you were fortunate enough to have one, was your transportation, so it took time and effort to visit your neighbors.

Loneliness was a fact of life, and we may see that in photographs from the time. Look at the photograph of the John Curry sod house in 1886. Do you see the birdcage? Both the birds and their cages are fragile objects. Why would families go to all the trouble to transport them across hundreds of miles of bumpy trails in rough wagons? Well, the birds may have helped cope with the loneliness. Canaries offered a bright spot of color in a landscape that the settlers saw as endlessly green and brown. And their songs were welcome, because there were few native birds on the treeless prairies.

Later, beginning in the 1870s, brochures and publications praised the plentiful rainfall and fertile land. Professor Samuel Aughey, from the University of Nebraska, declared the state’s rainfall was enough to grow good crops and, in fact, was increasing. "Rainfall follows the plow," he declared in an 1880 book, Sketches of the Physical Geography and Geology of Nebraska. The problem, he said, was that rain would hit the hard sod and run off and into the rivers. If farmers broke up the sod, the rain would soak in and then return to the air as it evaporated. With more moisture in the air, more rain would fall, continuing the cycle. Professor Aughey and others wrote and spoke far and wide. The railroads used their trains to distribute Aughey’s book and others to future settlers. And for a few relatively wet years, the theory seemed to be true. Rainfall was increasing. But when the next cycle of dry years hit, many new settlers learned the truth in hard ways. Nebraska could support agriculture but not using the same techniques they had learned in more humid climates.