It was called an “unusual suggestion”.

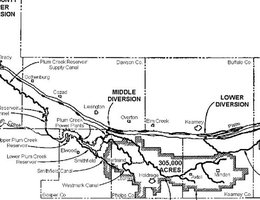

The suggestion was “supplemental irrigation”, and it was proposed in 1913 by C.W. McConaughy, a grain merchant and mayor of Holdrege, Neb. The plan called for Platte River water to be brought via canals to south-central Nebraska farmland during the spring and fall when river flows were at their highest. The water would be used to soak the soil, allowing crops to draw upon the stored water during the growing season.

“When I have stood and seen for weeks great volumes of water rolling down the Platte in the flood season to become a nuisance in the lower Mississippi, and when I have seen the semi-arid lands in our counties suffering and thirsting for water during the crop-growing season, my heart has been set on fire with a vision. I have a vision of what Nebraska can be and ought to be if a combined effort were made by all of its citizens (to build an irrigation project).” — C.W. McConaughy, in speech promoting the Tri-County Project.

McConaughy’s inspiration for supplemental irrigation came one day as he drove home from Elm Creek through farm country north of Holdrege. He noticed a field of wheat with spots where the wheat grew tall with long heads. In other places, the wheat was stunted and headed out before maturity. After locating the owner of the field, McConaughy found that shocks of corn had been left in the field over the winter and drifts of snow had collected around the shocks. When the snow melted and the water soaked into the soil, it was in these places where the wheat grew best.

Another influential figure in the formative days of the Central District was George P. Kingsley, a Minden banker and businessman. Kingsley heard McConaughy speak about the wonders that could result for agriculture in the area from just a small amount of additional water. From that point on, he dedicated his time, energy, and considerable talents to bringing irrigation to the area. From 1913 until his death in 1929, Kingsley worked to make the dream of irrigation a reality.

Prior to the onset of construction of Lake McConaughy and Kingsley Dam in 1936, obstacles to the project’s success came in the form of obtaining federal funds, competition for state water rights, opposition from private power companies in Nebraska, and skepticism from farmers fed by a lack of understanding of the project and misinformation from project opponents. McConaughy, Kingsley, and other irrigation proponents worked tirelessly to overcome the obstacles.

McConaughy supported construction of two storage reservoirs on Plum Creek in northern Gosper County. The reservoirs would store water diverted from the nearby Platte River. However, a lawsuit filed by opponents of the project resulted in a ruling by the Nebraska Supreme Court that prohibited the Central District from delivering water to land outside the Platte River basin. This eliminated almost two-thirds of the acres from the planned delivery area, making the project uneconomical as proposed.

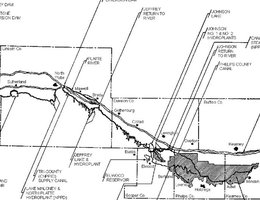

Plans for the project were quickly redesigned. Routes of canals were changed, and the hydroplants were relocated. More importantly, the two Plum Creek reservoirs were dropped in favor of a reservoir site on the North Platte River north of Ogallala, Nebraska. The new plan included construction of a huge dam across the river and convinced engineers who were evaluating the project that the project would provide enough storage water for Central’s project as well as other irrigation canals in the Platte Valley. The larger storage reservoir and the new sites for the hydroplants also allowed the project to generate and sell more electricity. This made up for the loss of revenue that would have come from delivering irrigation water to the lands removed from the project’s service area by the Supreme Court’s decision.

The decision to build the dam (now known as Kingsley Dam) at the new site led to the resignation from the Tri-County board of directors of one of its founders and staunchest supporters. C.W. McConaughy could not accept the decision to abandon plans for the Plum Creek reservoirs in favor of a different reservoir site. McConaughy lived to see construction of much of the project for which he had worked so hard, but died on April 15, 1941, only a few months before the completion and formal dedication of Kingsley Dam. The dam formed the lake that, ironically, now bears his name: Lake McConaughy.