As more and more nuclear weapons were being built, put into planes and on top of rockets, there were individuals who thought that the doctrine of deterrence through MAD — Mutually Assured Destruction — was just that, mad. They felt that it was better to negotiate to resolve differences with communist governments rather than threaten to destroy each other.

In 1948, U.S. war resisters burned their draft cards to protest the first peacetime draft. In 1949, Russia exploded its first atomic bomb and China fell to the communists. That same year, British peace advocates set up a Commission for Non-Violence.

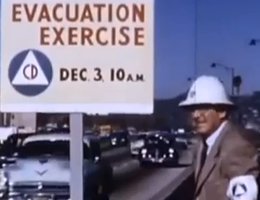

In 1953, the new U.S. Civil Defense Act required cities to simulate nuclear air raids. In cities like New York, air raid sirens wailed, and Times Square emptied as New Yorkers filed into subway tunnels and fallout shelters. Not a person or a moving vehicle remained in the street. Peace activists decided these annual drills were designed to placate citizens into thinking that nuclear war as survivable and winnable. In June, 1955, when the sirens wailed, around 30 activists gathered in front of City Hall and refused to go to the shelters. They were reprimanded. The next year, they were arrested. By 1960, their numbers had swollen to 500. In 1961, there were 2,000. In 1962, the drills were cancelled.

In 1958, members of a new group called the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) tried to sail a small boat into the area of an atomic bomb test in the South Pacific. By putting themselves in harms way, they thought the military would be forced to call off the test. They were arrested in Hawaii before they got to the test site. But, the captain of another boat heard about the arrests and decided to carry on the protest. They, too, were arrested before they could reach the test area.

The CNVA became a major peace activist group, and their second major protest was held in Nebraska. In 1959, SAC was building a series of Atlas missile complexes around Lincoln and Omaha. National and local activists decided to try to stop the construction. The group included at least 80 local activists and over 35 national leaders who came to Omaha. On May 21, 1959, the group sent a letter to President Eisenhower asking him to renounce the use of military force as a means of solving international conflict. They said it was their religious and patriotic duty not to remain passive spectators while the weapons of nuclear warfare were being deployed in the U.S. They assured Eisenhower that their actions would be taken in the spirit of nonviolence, and said that some of their members might engage in civil disobedience. They said they were following the spirit of Mohandas Gandhi and were willing to accept imprisonment.

The effort was called "Omaha Action". It began on June 18 with meetings in both Omaha and Lincoln to talk about the dangers of nuclear war and non-violent ways to protest. Two days later, protesters marched up to Mead from Lincoln and Omaha, a distance of 30 to 40 miles. For the rest of June and much of July, protestors maintained a 24-hour vigil outside the missile site.

Some protestors used civil disobedience tactics to drive their message home. Some stood in front of trucks attempting to deliver parts to the silo. They were arrested. Others climbed the fence surrounding the site. At least four were tried and given the maximum sentence of six months in federal prison and a $500 fine. Others were sentenced to local jails.

The protestors explained that "we live on the brink of war," and that allowing missile bases to be built would push us closer to war.

"The insane arms race continues. It is justified on the grounds of ‘deterrence’: each side builds its arsenal of satanic weapons, not to use them, but only to keep the other side from using his. If people trusted this, they would feel secure. Actually, the arms race is preparation for genocide — mass extermination — and in their hearts many people sense this."

Even though the organized vigil and civil disobedience ended in August, the organizers suggested ways for other citizens to protest.

"Citizens can find new ways to convince those in public offices that our country’s goal should be withdrawal, unilaterally if necessary, from all preparations for war, thus setting an example which might break the vicious circle of destruction, which now binds mankind. Scientists can refuse to work on weapons of mass destruction; laborers can refuse to build missile bases and other military installations. Union members can strike against military projects, then choose peaceful, constructive work. Youths can refuse to submit to conscription. Taxpayers can refuse to provide funds to make weapons of genocide; Church members can work to bring the action of their churches in line with their profession of faith in the way of love."