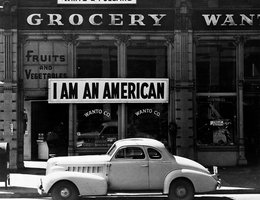

What is it like to be born and raised an American, but to be considered an enemy because of where your parents were born? That’s what happened to many Japanese Americans in World War II.

Racism and war hysteria motivated the U.S. government to forcibly move more than 120,000 Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast to internment camps between 1942 and 1945. Nebraska’s central location kept its Japanese American citizens comparably safe from this process, although some were restricted from accessing their bank accounts.

.

Ben Kuroki was born in Hershey, Nebraska in 1918, where his family grew potatoes. When he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor, he wanted to join the fight against the Japanese. Ben felt it was his duty to prove his loyalty and love for his native country, the United States. In the military, he faced prejudice and sometimes danger from some of his fellow soldiers. But his crew trusted and relied on Ben, and many others vouched for him as a loyal American.

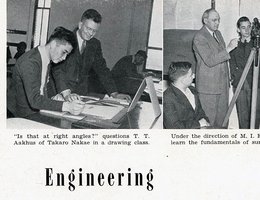

Lt. Kei Tanahashi was another Japanese American war hero. He attended the University of Nebraska at Lincoln before joining the U.S. military. This notice appeared on page 42 of The Cornhusker, the Yearbook of the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, 1945. (Heart Mountain, Wyoming was one of the locations for internment or relocation camps.)

"Lt. Kei Tanahashi, ex ’46, Heart Mountain, Wyoming, a Nisei officer, was killed in Italy in July, 1944. Lt. Tanahashi, mortally wounded while leading his troops in hostile action, died while directing operations against snipers. He wrote ‘when this business is taken care of, we will live together as good Americans.’ "

Lt. Kei Tanahashi was another Japanese American war hero. He attended the University of Nebraska at Lincoln before joining the U.S. military. This notice appeared on page 42 of

The Cornhusker

, the Yearbook of the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, 1945. (Heart Mountain, Wyoming was one of the locations for internment or relocation camps.)

"Lt. Kei Tanahashi, ex ’46, Heart Mountain, Wyoming, a Nisei officer, was killed in Italy in July, 1944. Lt. Tanahashi, mortally wounded while leading his troops in hostile action, died while directing operations against snipers. He wrote ‘when this business is taken care of, we will live together as good Americans.’ "

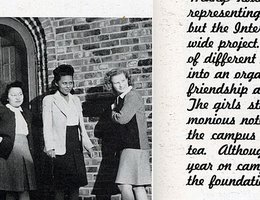

In 1940, the median age of Nisei (those people born in America, but of Japanese parents) was seventeen. When Japanese Americans had to start selling their belongings to move to the camps, some young Nisei began writing to universities in the heartland. Many universities rejected or forbade them admission. In 1942, the University of Nebraska Board of Regents officially approved admitting "Japanese students" if the FBI cleared the applicants. A quota of no more than 50 students at a time was set and rigidly followed.

In 1940, the median age of Nisei (those people born in America, but of Japanese parents) was seventeen. When Japanese Americans had to start selling their belongings to move to the camps, some young Nisei began writing to universities in the heartland. Many universities rejected or forbade them admission. In 1942, the University of Nebraska Board of Regents officially approved admitting "Japanese students" if the FBI cleared the applicants. A quota of no more than 50 students at a time was set and rigidly followed.

Many Nisei felt they were treated well in Lincoln. Roy Deguchi told the story of a family who invited him to church, picnics, and their home. On one visit, he learned that their oldest son was on the Pacific front. Their kindness to someone of Japanese descent illustrated what he called, "the Nebraska spirit, a sense of fairness."

Not everyone was happy to have the Japanese American students here. The assistant dean of women, Elsie Ford Piper, vigorously enforced segregation in the women’s dormitories. In 1944, the Board of Regents made that segregation official policy, claiming it would avoid "interracial agitation or interracial questions whenever possible." Although there was some ever present resistance to the Nisei relocation in Nebraska, by the end of the war, the University of Nebraska had welcomed the third largest number of students; only the universities of Utah and Colorado admitted more.