On March 24, 1942, Joan Catalano was the first woman inspector to be hired by Martin-Nebraska. Women were later hired as inspectors in receiving, detail manufacturing, general assembly, finishing and planting, hangars and flight test, and modifications departments at the plant.

However, there were ominous indications that these gains might be temporary. Over 80% of the women hired by the plant were placed in jobs lowest on the classification tables. The Martin Star, published monthly at the Martin-Baltimore plant, praised women’s "inborn quality for patience and their ability to make monotony an interesting thing", but went on to say that their intuition and originality could best be used at home:

"When certain foods and clothing become shortages [scarce] they [ideal women plant workers] cheerfully give up what they might need for their men at the front. . . . They spendtheir evenings and spare time mending and restyling clothes, repairing their home appliances, knitting sweaters for their kiddies, and stretching their food rationing points."

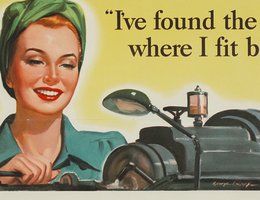

In November of 1944 more than 40% of the Martin Bomber Plant’s nearly 12,000 employees were women. It was Nebraska’s largest recruiter of women war workers. At first, many of the women did not have the basic skills necessary for the jobs. Less than 10% of them had any extensive experience with machinery. But the Martin Company wanted to employ women on the same basis as men and declared that all "Martineers" were equal. Training classes and improvement groups brought the women’s skills to the required level. That goal became official policy.

Official Policy of the Martin Plant"Since the ratio of women to men in the entire industry, now 1 to 8, must soon reach 4 to 8 in order to fill places left by men inducted into the armed forces, the largest training job of all is that of preparing women for shops and assembly lines."

For many new members of the workforce, many of them migrating from rural areas to the city, new jobs meant new social pressures.

"I lived with my parents, while he [husband, Lovern Blacksher] was in welding school at Steele City, Nebraska, and then when he got his job at Martin, Nebraska [Bomber Plant], then we found housing — a little apartment — in Plattsmouth, Nebraska. We weren’t too enthused about living in Omaha because we were country-reared and so on. Many of the private homes were opened to people because housing was very difficult. We had two small rooms which were normally bedrooms in the upstairs of a home. One was fixed as a kitchenette, and the other was the bedroom. Very tiny closet and we shared a bathroom with another couple who lived on the second floor of the same house. . . . Each couple was given one shelf in the landlady’s refrigerator downstairs. We got along fine there." — Pauline Blacksher, Plattsmouth Martin Bomber Plant worker.

Women were motivated not only by patriotism and the desire for high wages. They gained a sense of community from participating in such an important mission. Without their labors, the U.S. war economy would never have been able to produce the military hardware needed to win the war. Their role in the workplace sparked the beginning of a change not only in the working roles of men and women, but in the living styles and home duties of both sexes.