Through the years, a variety of laws were passed in Nebraska to limit the sale of alcoholic beverages. But until the second decade of the new century, these laws all fell short of outright prohibition.

Early in the fight, prohibitionists pushed for a "county option" law that would permit a counties — rather than local cities — to determine whether they would be wet or dry. It was just too hard to outlaw alcohol town by town. But, the bill was defeated by the anti-prohibition forces.

The prohibitionists did not give up. In 1909, they launched a campaign to pass a so-called "daylight saloon bill" which would limit the operation of saloons to daylight hours. The proposal was very similar to one passed in the city of Lincoln. The move unleashed a storm of activity from both sides of the issue.

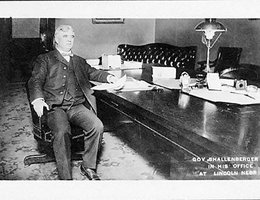

Gov. Ashton Shallenberger’s stand on the bill was unknown, so he was besieged with petitions and strong lobbying from various pressure groups. A former governor, William A. Poynter, appeared in Shallenberger’s office in April of 1909 to urge his colleague to sign the daylight saloon bill.

Poynter told Shallenberger, "The saloon is the rallying point, the incubator of crime. If an officer wishes to catch criminals, he goes there to find them. Let us curtail the hours, thereby curtailing the drink habit and crime which follows in its wake." Unfortunately, after his passionate appeal, the former governor died of heart failure.

The Lincoln newspapers of the period were convinced that Omaha saloons and breweries were the leading forces in opposing the daylight saloon bill. The Nebraska State Journal, Lincoln’s largest newspaper was generally against saloons (although they were not in favor of immediate prohibition). The Journal was suspicious of Omaha’s breweries:

"[Omaha’s] brewers are sending their agents into every city and town in Nebraska to destroy local restriction on the sale of liquor. The greatest danger to Lincoln’s 7 o’clock closing law has been the money of Omaha brewers . . . are ready to drop in here at the critical moment to turn the scale in a close election."

The growing power of the brewing industry was real. There was a nationwide trend towards consolidation of industry. Large firms were swallowing smaller firms. Between 1899 and 1909, the number of malt liquor breweries in the state had declined from 19 to 14. While the number of businesses was declining the number of employees and value of the products was going up. Omaha’s breweries, especially, were booming. In 1909, there were five establishments owned by one man — Charles Metz. He threatened to lay off a third of his labor force if the 1909 daylight saloon bill was signed.

Metz declared, "If the very life of the city is not to be throttled, this bill must not be signed."

The Nebraska State Journal responded,

"The prosperity of the great city of Omaha, it appears, is not founded . . . upon the trade of half a dozen mighty states in the central west. It rests upon the foam in the tops of beer glasses, and when it is blown away the whole structure comes tumbling down to the ground in a hopeless wreck."

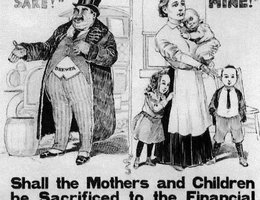

Some "wets" did fear that closing or restricting saloons would mean a decline in business activity. However, the "drys" believed just the opposite. They were convinced that money once wasted in saloons would find its way into the legitimate businesses of the state.

Despite the opposition of the brewery industry and others, the "daylight saloon bill" narrowly passed the state legislature on April 3, 1909. Gov. Shallenberger signed it into law shortly after.

The temperance movement in Nebraska was still not satisfied. They wanted a total ban on alcohol. Finally, in 1916 Nebraska voters approved a statewide prohibition amendment. Prohibition passed in Nebraska almost simultaneously with limited woman suffrage, and with the full support of the Nebraska Woman Suffrage Association. By law, there would be no more booze when the law formally went into effect in 1917.

Nationally, the prohibition forces were given a boost by America’s entry into World War I in 1917. The war had a two-fold effect. First, it increased the demand for grain products as a source of food for the soldiers — therefore, the "drys" argued that grains shouldn’t be wasted in the manufacturing of alcohol. Second, the war also weakened of the political power of the German-Americans who generally had supported the "wet" cause. America was at war with Germany, so anything associated with Germany came under attack. As the loyalty of German-American citizens came under question, their political power decreased. It was less fashionable to argue for the continued use of alcohol.

National prohibition would be secured with the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919. Alcohol was outlawed, and the nation began what became known as a "Noble Experiment."