The temperance movement in Lincoln of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a good example of how prohibition affected towns and cities across the nation. Lincoln had active temperance groups who believed the saloon was an evil institution that undermined the traditional values of family, thrift, social order and community prosperity. But the city also had groups who regarded alcohol as a normal part of social life and saw nothing wrong with having a drink, now and then.

The Lincoln newspapers of the period took the position that democracy was threatened because the saloon patrons voted the way saloon owners instructed them to vote. They saw saloons and breweries dominating the local and state political scenes.

The conflict over prohibition produced divisions within the community — the city was divided over the prohibition issue into different ethnic groups, social classes, religions, and desire for political reform. It was not a homogeneous city when it came to regulating the sale of alcohol.

In 1902, the supporters of prohibition were able to get Lincoln city officials to pass a progressive excise tax for Lincoln saloons. The excise tax, also called a license fee, was gradually increased to $1,500 per saloon. Saloon’’s had to pay the tax in order to serve alcohol. The plan was to create high license fees that would reduce the total number of saloons. The law also limited the number of hours of operation by the saloons — 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and limited where saloons could be built in Lincoln.

But high taxes and daylight operating hours was not the ultimate goal of prohibition forces, and the battle waged back and forth.

In 1909, the citizens of Lincoln were presented with three choices in the May 4 election.

The prohibition resolution won with a bare majority of 51 percent.

Prohibition was back on the ballot in 1910, and the prohibitionists once again prevailed with a slim margin of victory.

It was back again in 1911, and this time, those in favor of alcohol — the "wets" — defeated the "drys." But, it was a hollow victory because there was a return to strict licensing which was geared toward the eventual elimination of the saloon.

— By T. J. Merryman, from Nebraska’s Favorite Temperance Rallying Songs (1908), compiled by Mrs. Frances B. Heald, Nebraska WCTU president.

The prohibitionists, the "drys", in Lincoln tended to reside in relatively affluent neighborhoods and were members of the city’s professional and local business elite. They were in the middle and upper socioeconomic classes and tended to be strong church members of Protestant denominations like the Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Baptist, and Christian.

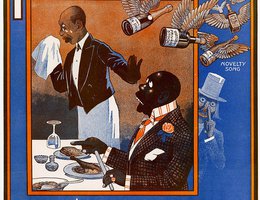

Ethnicity also played a major role in the prohibition movement. A distinction was made between the "new" and "old" immigrants. The loyal prohibitionist was likely to be native-born, that is, born in America. The early immigrant ancestors of these second- or third-generation Americans were viewed as strong-minded and moral people. The recent immigrants were more likely to be viewed as a threat to the values of sober middle-class citizens.

Ethnic stereotypes also were common. Germans, Czechs, Greeks Russians, and the Irish were viewed as the tools of the saloon and brewers’ interests. Saloons and foreigners went hand-in-hand in this stereotype. African Americans were also portrayed as drinkers.

The anti-prohibition forces, the "wets", were more likely to live in the less affluent areas of the community and represent the working class. Many belonged to the Catholic and Lutheran Churches and were of Russian and German backgrounds.

Thomas Bonacum, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Lincoln, expressed the views of the Catholic Church on the issue of prohibition in a letter to Governor Ashton C. Shallenberger in 1909. He urged the governor to sign a bill that would limit the number of hours a saloon could sell alcohol to those hours of daylight. He also cautioned against any further legislation that might lead to prohibition. Bonacum viewed the daylight bill as an "eminently wise and salutary" measure that was "calculated to lessen the abuses of the liquor traffic." The Bishop said that the bill removed "the necessity for any future legislation which might be harmful to the best interest of our commonwealth." In other words, he favored some regulation, but not a total ban on alcohol.

While the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League represented the prohibitionists, the anti-prohibition forces also had organizations that defended their views. The Personal Liberty League enjoyed considerable influence and questioned the legality of any level of government interfering in the personal drinking habits of individual citizens. After all morality was the concern of the individual and the church, not public institutions like governments.

The temperance campaign committee responded:"The public safety, the public health, and the public morals are the supreme concern of the government. The saloon, as everyone knows, endangers the public safety, destroys the public health, and corrupts the public morals. Therefore, the government that is true to itself must outlaw and inhibit the saloon."