"The Populists didn’t feel that they could get anywhere in their parties.So, they organized their own." — Annabel Beal

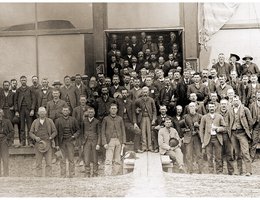

In July, 1890, more than 800 delegates from 69 Nebraska counties met at Bohanan’s Hall in Lincoln. They were there to organize a new political party to advance their ideas into law. They called the group the Populist Party. Their party platform — the policies they advocated for voters — included most of the Farmers’ Alliance platform. The Populists also wanted government ownership of railroads and the telegraph, land reform, free silver coinage and lower taxes. But they also added planks calling for the adoption of a secret ballot in elections, freight rates in law that were no higher than those in Iowa, pensions for old soldiers, an eight-hour work day for laborers (but not for farmers), and an increase in the amount of money in circulation to an equivalent of $50 per person in the country. In July, the Populists met again, this time in Columbus, to nominate candidates.

The People’s Convention nominated a full slate of candidates, including the president of the Farmers’ Alliance, John H. Powers of Trenton, as the Populist candidate for governor of Nebraska. The campaign that followed was exciting. With a withering drought that summer, Alliance orators declared over and over, "We farmers raised no crops, so we’ll just raise hell." A Populist picnic at Cushman Park in Lincoln drew 20,000 people. In the little town of Wymore, 1,050 farmer’s wagons were counted in a Populist parade. That same day in Hastings, 1,600 were counted. Slogans, songs and weekly newspaper coverage pushed the Populist cause.

The state’s old politicians and major daily newspapers, on the other hand, called the Populists "hay seeds," "horny handed sons of toil," "political thugs," and "hogs in the parlor." It didn’t matter.

When the election returns came back in November, 1890, the Republican Party had lost nearly every race for the first time since statehood.

The governor’s race soon proved to be important. During the legislative session that followed, populists passed a law mandating secret ballots in state elections. They provided free textbooks to schools and passed the state’s first compulsory education law. For the first time, all young Nebraskans were provided a common school education. They passed a public fund deposit law and mutual insurance acts. They passed a law establishing the eight hour day as a legal day’s work, except on the farm, but that law was struck down by the state Supreme Court. One of the major Populist goals was the reduction in railroad freight rates. After an all-out fight in the legislature, a bill cutting rates to those enforced in Iowa finally passed. But Democratic Governor Boyd vetoed the bill. He thought it would bankrupt every railroad in the state since Iowa’s tonnage of goods shipped was four times that in Nebraska. The Populists weren’t able to get the three-fifths majority vote to override the veto.

In 1892, the Populists were full of hope. The party had organized nationally and nominated a candidate for president. In Nebraska, they nominated a more seasoned politician as their candidate for governor, Charles H. Van Wyck. But the Democrats nominated the conservative tree-planter J. Sterling Morton as their candidate, and Morton campaigned primarily against the Populists. As a result, the Republican Lorenzo Crounse was elected governor. Democrat Bryan and Populists McKeigahan and Kem all returned to Congress, but three new seats created by the 1890 Census all went to Republicans. The one bright spot for the Populists was that they were able to re-unite with the Democrats in the state legislature and they elected a Populist judge from Madison County, William V. Allen, to the United States Senate.

In 1894, the "Silver Tongued Orator" William Jennings Bryan changed the political landscape. That year, Bryan became editor of the state’s most powerful Democratic paper, the Omaha World-Herald. A drought had resulted in crop failures for two years. And many farmers were convinced that the only thing that would save them was the free coinage of silver. At the Democratic convention in 1894, Bryan was able to fuse the Democratic Party with the Populist Party. The convention nominated an entire Populist state ticket. The only prominent Democrat on the ticket was Bryan himself, nominated for U.S. Senate. In the election, the Democrat/Populist Silas A. Holcomb won the election for governor. But, the Republicans won almost every other state office. Omer Madison Kem was the only Populist re-elected. And in the state legislature Republicans easily elected a lawyer for the Union Pacific Railroad, John Thurston, to the U.S. Senate. That must have been particularly galling for the Populists.

Holcomb was re-elected governor in 1896 and another Populist, William Poynter, was elected in 1898. The party was able to push through many of their ideas, but they failed to enact their most important proposals. And the party — as an independent third party — was never able to gain complete control of the state government. The party dissolved in 1908. Their biggest influence may have come through their fusion with the Democrats and the launching pad that provided for William Jennings Bryan.